Book Review: Origins: Ruy Lopez - Book II: Specialty Lines after 3...a6

Everything except the absolute main lines.

Introduction

Cyrus and Carsten are back with their second entry into the Origins: Ruy Lopez series, which tackles everything in the Ruy Lopez opening after 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 (also known as the “Morphy Defense”).

The path to the main line in the Spanish Game has many forks where either White or Black can deviate. To wit, the following opening lines are covered and organized as follows:

The Exchange Variation (4.Bxc6 — everything afterward follows 4.Ba4)

The Steinitz Deferred Variations (Black plays an early d6, and often fianchettos their kingside bishop with g6 and Bg7).

The Arkhangelsk/Moller Variations (in which Black plays any combination of Bb7 and Bc5 — since these plans can be mixed, it makes sense to put them under one chapter)

The Delayed Schliemann (4…f5?!)

The Norwegian Defense (4…b5)

Following 4.Ba4 Nf6, the early Qe2 variations (Worrall and Wormald Attacks) and 5.d4 (Mackenzie variations)

The Open Variation (5…Nxe4)

White’s “unusual” sixth moves after 5…Be7: 6.d3 (Martinez Variation), 6.Bxc6 (Deferred Exchange Variation), and 6.d4 (Center Attack)

6.Re1 is the absolute main line where most theoretical blood has been spilt, so it makes sense for them to reserve an entire book dedicated to the myriad variations such as the Chigorin Defense, Breyer Variation, Marshall Attack(!), Zaitsev Variations, etc., etc. There’s a lot there — they have their work cut out for them!

Did you miss the first book? You can read that review here:

Book Content

A lot of what I said about the writing style of their first foray into this series applies to this second expedition: Cyrus seems to have the main voice in the annotations, and his sense of humor is either a bright or dark spot depending on the reader’s tastes. The selection of games is instructive and generally also entertaining. Every important variation gets at least one historical example of how it was played at first, and then following in chronological order you see how the theory of that variation evolved. The authors do not purport to bring an entire repertoire for the reader, and they aren’t trying to stand on the cutting edge of novel chess computer ideas. They just want you to understand the general ideas behind the opening through lots of examples. You won’t find many novelties here, but on occasion they may point out an “untried” move.

The book is organized rather well and starts off on good footing with the Exchange Variation chapter. The first game is Lasker - Capablanca, St. Petersburg, 1914, which is perhaps the most famous example of this variation, in which the World Champion pressed hard against the Cuban upstart in a must-win situation to eventually take first place. This happens to be one of my favorite games of the pre-war time period, but it’s also instructive to show how White can play the Exchange for a win and that Black cannot defend passively but must go for active counterplay, a lesson that even Capa had to learn. Then comes the next treat — seeing Fischer batter Spassky using the Exchange Spanish in their 1992 rematch, a practical miniature with a beautiful finish.

Then comes everything after 4.Ba4. Every deviation from 4…Nf6 is covered well here: Steinitz Deferred (4…d6) both in its Kings Indian Defense-esque and Fishing Pole trap variations, and others; the Arkhangelsk and Moller complex, the Delayed Schliemann (frankly, I’m not sure this line deserved its own chapter) and Norwegian Defense. These are all considered second-rate by the authors.

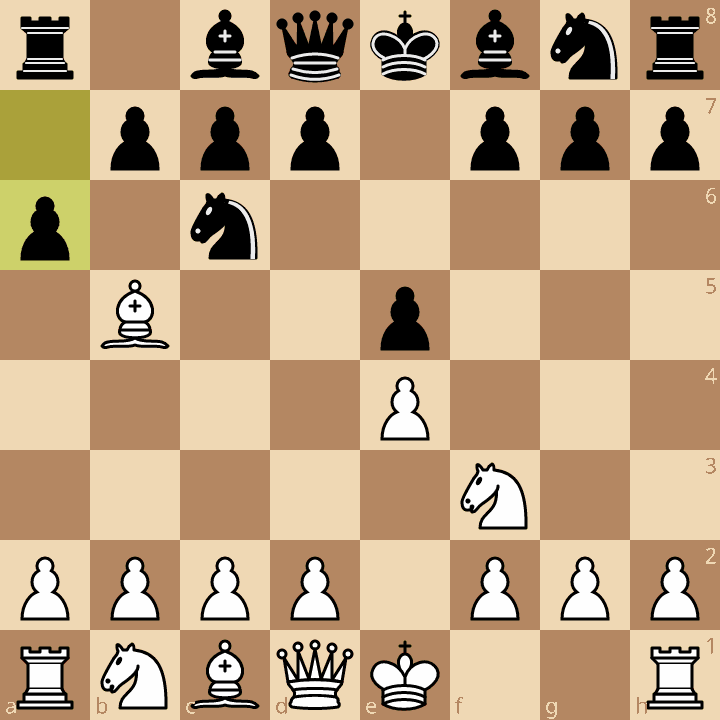

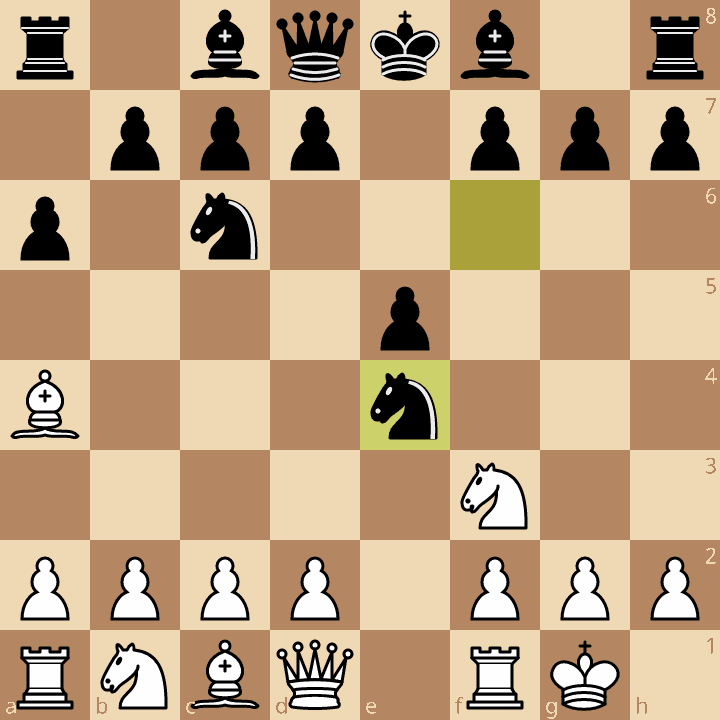

I have to say, in the defense of the Steinitz Deferred (which, yes, is part of my repertoire, why do you ask?), though they think White is better in the d5 lines of the Steinitz Deferred main line, the bishops don’t matter as much in closed positions and Black is generally fine without the light-squared bishop. It is interesting that Lakdawala and Hansen describe the below position as reminiscent of “the depirvation of Lent", even if they aren’t Catholic”, while Gawain Jones in his extremely excellent Chessable course calls this a good King’s Indian that stronger players with White tend to avoid. Lichess’s database shows that Black scores excellently in this position, but the authors picked a win for White. In the end, I appreciate the authors giving their opinions on the matter even when others may disagree.

After 4…Nf6, White has some sidelines involving an early Qe2 or 5.d4 push. These lines are covered in a bit of detail, and they explain the ideas behind them well, and why 5.O-O is to be preferred.

Once we get to 5.O-O, we get some delicious treats in the chapter on the Open Variation. Two heroes of 5…Nxe4 were Johannes Zukertort and Victor Kortchnoi. The authors make sure we get to see them both multiple times in action. Zuke’s games are impressive considering that this was his novelty he was showing off; but the games in which Karpov and Kortchnoi clashed left the deepest impression upon me. These games were electric, and this rivalry between the two can be felt even in the tension of the positions of these games. This was by far my favorite chapter in the book. It’s unfortunate that so many of these games, except for Zukertort’s and a single win by Mamedyarov vs Caruana, end in a loss for Black. I wish more examples of Black winning were included. However, this maybe also suggests why Black still overwhelmingly chooses the Closed defense with 5…Be7 at the highest levels. One other small critique I should give this chapter: I think that it was worth covering, even for a single game, both the Riga Variation (6.d4 exd4?! — White should know how to bust this dubious gambit) and 6…Be7 (they award this move a “?” but the difference in evaluation vs 6…b5, at depth 43 on Lichess’s Stockfish 16, is about 0.1).

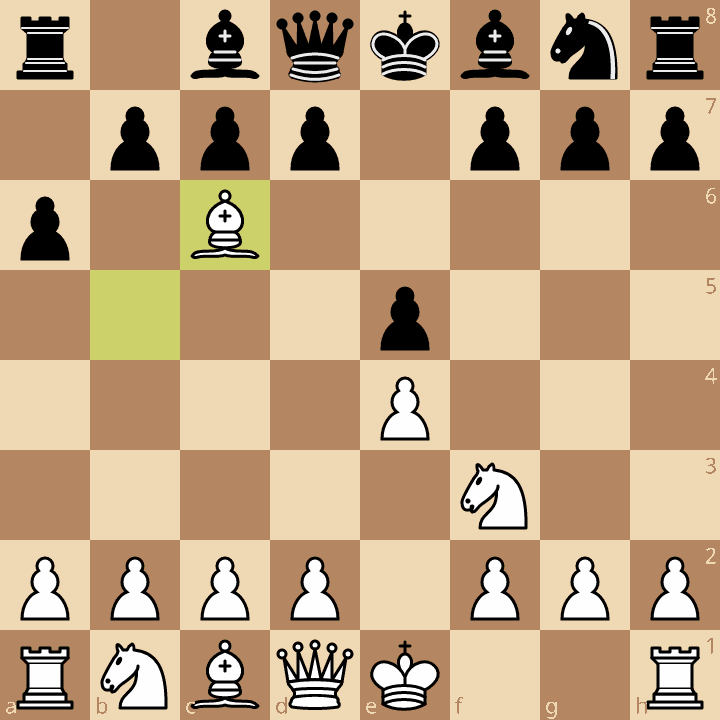

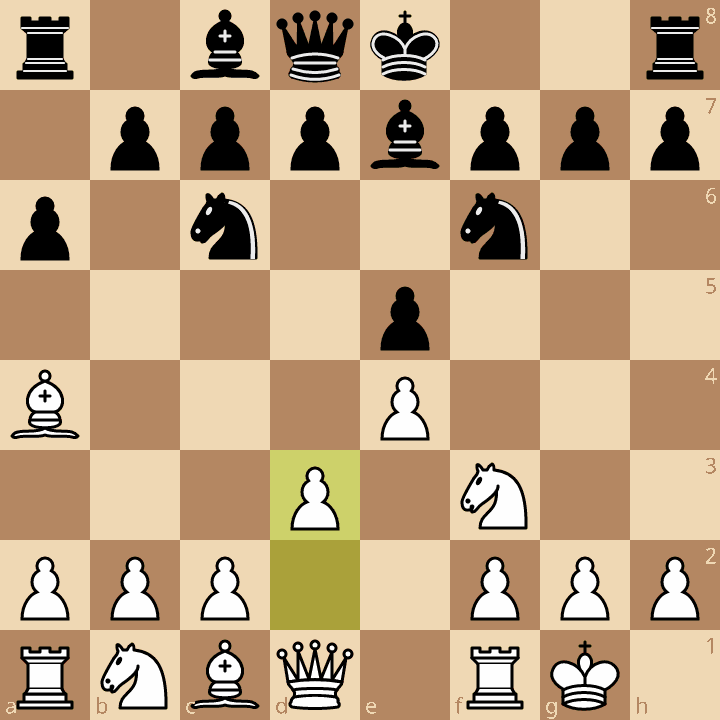

In the final chapter, we get a treatment to White’s “unusual” (their words) 6th moves. While I agree that 6.Bxc6 and 6.d4 are unusual, and not particularly good, I protest a little that 6.d3 (the Martinez Variation) is virtually relegated to the status of theoretical b-side, going so far as to claim “this move gives White no advantage” which is a bit misleading. In their defense, they also say “on the plus side, White dodges all sharper engine prep and gets the slow maneuvering game they want.” I think their main argument is that this move represents a loss of time over the main line 6.Re1, in which White may plan c3+d4 later, rather than spending time on d3 which is admittedly a slower move. 6.d3 is a serious move that has seen a lot of master play in recent years (one extremely instructive example was Giri-Artemiev in Round 1 of the Shenzhen Masters tournament, 2024):

If we have any doubts as to the veracity of this move, the authors themselves give us one extremely famous example in recent history: Nepomniachtchi - Ding, 2023 World Championship. Nepo may be the champion of this line in top-level chess today, given his liberal use of it in that match. I digress — the games in here are good. And I admit some ulterior motive that since 6.d3 is the move I play, I’d like to see it see more coverage one day — it deserved at least as much coverage as 5…Nxe4.

Favorite games from the book:

As far as selection of games, I already said it’s pretty good. Here were the games that I felt were best:

Game 1: Lasker-Capablanca

Game 2: Fischer-Spassky

Game 9: Smyslov-Euwe

Game 18: Morphy-Hammond (I noted this one in particular because Morphy is always fun to watch, but also, it’s rather rare to see him play the Spanish, so for historical reasons I thought this was a great inclusion)

Game 24: Rapport-Ding

Game 30: Duda-Tari

Game 31: Spassky-Taimanov

Game 40: Karpov-Kortchnoi

Game 41: Karpov-Kortchnoi

Game 43: Carlsen-Niemann

Game 51: Nepomniachtchi-Ding

Every game in this book deserves to be there, however, including one win by Lakdawala against the Open Variation, showing how White can get a quick win if Black is slow on the draw in that hyper-active defense:

For my fellow club players

Per the usual, this book is also loaded with practical advice for players looking to improve. Any player at the level where people are actually playing any theoretical move after 3…a6 4.Ba4 in the Ruy Lopez is a prime candidate for this one. It’s typical of Lakdawala’s books to include prompts such as Principle, or Calculation Exercise, Combination Alert, and others of that nature, to perk up the reader’s attention and look for the win or carefully consider the coming explanations. Even where there isn’t an immediate principle, being an attentive reader rewards with lots of wisdom they can take into any game, Ruy Lopez or not. Strikingly, they have this to say about studying chess theory in today’s day and age near the beginning of the book:

Being untethered from theory is no longer the same as being untethered from understanding. At the club level, players forget their theory all the time. This doesn’t mean you forget your understanding. This is why we go about in a progression from past to present since it’s all about recognizing the distinct architectural elements of the lines’ structures, plans, and typical tactical motives[sic] without worrying (too much!) about the details. How are we to memorize so many variables within the Lopez? The answer for the great majority of club players; we don’t. Just play through the games and absorb/understand rather than memorize.

Of course, this very good advice early in the book is immediately followed up by a bad joke. You can’t win ‘em all. There are still some genuinely humorous moments in the annotations that caught me off guard — it’s not all that dreadful — and sometimes it even seems accidental. One odd and possibly unintentionally humorous moment was where they cited a game between Lasker and Steinitz, from move 7 all the way to move 46, but anticlimactically ended it with “Lasker played on hopelessly for a few more moves.” Why not just show us the whole game — you’ve taken us this far!? But in general the humor improves as the book goes on — it has the same nagging edge that the Ruy Lopez does.

Conclusion

In the end, this is another solid entry into the promising Origins series. If Carsten and/or Cyrus plan on doing more of these and in different lines, I’d be very interested in those — knowing the story of an opening can go a long way towards understanding it and playing it the right way. And of course, I’m looking forward to the third and final entry with regard to the Ruy Lopez, where they discuss 6.Re1 which is a gargantuan theoretical beast of its own.