Book Review: "Origins: Ruy Lopez - Book I: Black Avoids 3…a6" by IM Cyrus Lakdawala and FM Carsten Hansen

A nice collection of games in the Spanish Opening, with an emphasis on the Berlin Defense.

Introduction

As far as opening books go, I have always eschewed them in favor of Chessable. This is mostly out of comfort and convenience, since Chessable was the first product I used to study chess openings in earnest. However, when I saw what this book’s premise was (which was to discuss the “origin” of each variation), I decided to give it a shot. The authors make a point not to discuss theoretical novelties (which appear and disappear in a flash in the modern era), but rather give you a practical understanding of the typical plans, tactics, and ideas in the opening, as well as important historical context. One last thing they mention is that today’s club player games tend to reflect very early master play, so knowing how to exploit common errors will lead to more won games. This seems like very sound reasoning.

This book has two authors: The prolific chess writer IM Cyrus Lakdawala and the also-popular FM (and FIDE Trainer) Carsten Hansen. I’ve read more Cyrus than Carsten, but my impression of Carsten is that he likes to look for interesting sidelines and embarrass others with them over the board, having put out books on things like 1.b4. To me, the main voice of the book (and sense of humor) appears to be Lakdawala, but I think that Hansen must have done a lot of work picking interesting games to include in this little collection of model games.

Previous readers of Lakdawala know what to expect in the annotations: a very oddball sense of humor. I feel like this was most jarring at the beginning of the book but was increasingly turned down in intensity as things went on. It’s not that I dislike humor, just that sometimes it wasn’t always in good taste. I’m not sure Lakdawala considers himself as having good taste to begin with; I’m just saying that in my kindle edition there were at least a couple moments where I highlighted some text just to note “Why?”. If you’re a Lakdawala fan, this isn’t a problem. If you’re new, YMMV. But if you’re decidedly not a fan of his divisive irreverence, you should move along.

Why play the Ruy Lopez?

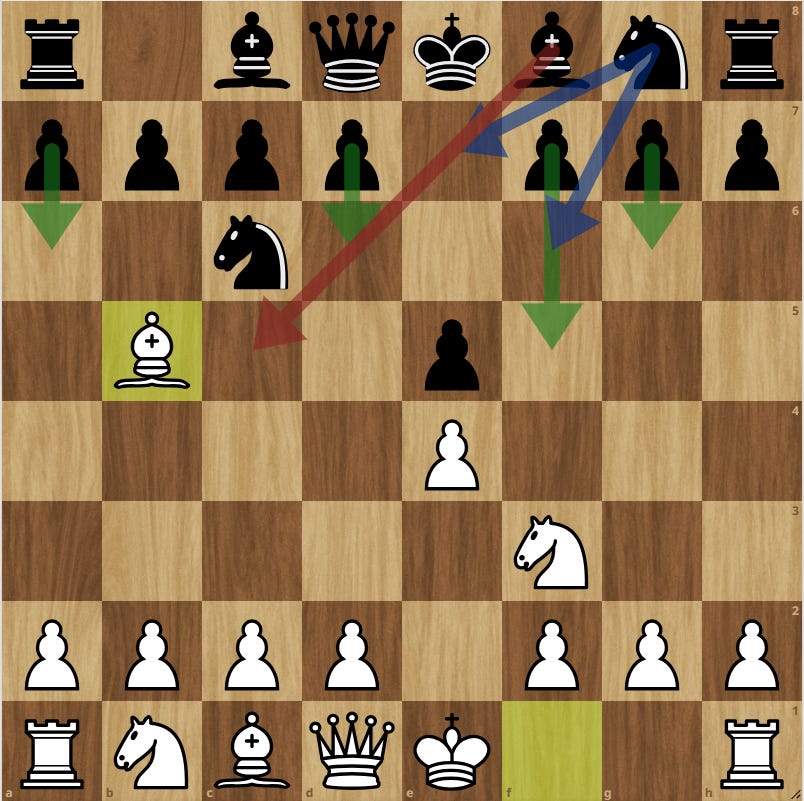

One “problem” with the Ruy Lopez is that it represents a comparably astronomical amount of chess theory compared to both the Italian (3.Bc4) and the Scotch (3.d4). Ofttimes players are just told in an unqualified manner to simply avoid playing it because of this theoretical load. If you look at the below screenshot, I’ve highlighted all of the possible moves black could go for on move 3. Also, some of these moves are combined in some order to reach other variations. Both sides’ options tend to broaden on move 4 and following as well, but at a very superficial level it’s easy to see that this opening is still rather complex.

Now, the truth is that many of these moves have trusted responses that you might need to learn to memorize in order to neutralize any threats; but generally opening theory study time beyond that for sidelines like these tend to be a waste of time for the club player. That is true for the Ruy Lopez, but it’s also true for any opening either side could choose. So, you can learn the Ruy Lopez (a.k.a. The "Spanish Game”), even as a beginner or amateur, and it will be good for your chess. And unlike some openings, you won’t grow beyond its theoretical bounds. As fellow chess improver Neal Bruce likes to say, it’s a Cadillac opening. It is a matter of taste, but there isn’t a reason not to study the Ruy Lopez if you want to learn how to play it. Just avoid studying 23-move deep novelties and you’ll avoid wasting your time.

Book Content

Origins: Ruy Lopez - Book I: Black Avoids 3…a6 contains 51 fully annotated games, one main variation per chapter, each chapter arranged in chronological order. The annotations are well-placed, with lots of notes about alternative ideas (and whether you’ll look at them in the near future). This is the first part of a three part series. The authors have their work cut out for them, and I’m looking forward to what comes next!

The idea behind Origins was already discussed in the introduction, so as far as content, this book handles everything on Black’s third move in the Ruy Lopez after 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 that is not 3…a6. The primary focus of the book is the Berlin Defense, but it also handles several other sidelines. To wit: Bird’s Defense (3…Nd4), Old Steinitz Defense (3…d6), Schliemann Defense/Jaenisch Gambit (3…f5), Classical Defense (3…Bc5), Steinitz Fianchetto Variation (3…g6), Cozio Variation (3…Nge7), and the Four Knights Spanish. These are all the reasonable responses, so they get a chapter dedicated to them, usually including a few games a piece. Less reputed defenses get some lip service in the first annotated game in the collection but that’s about it. They seem to do this for a bit of humorous thoroughness.

The games from the actually decent variations were all rather instructive on how to and how not to play those particular openings. As well, because this book isn’t about squeezing out the last molecule of water from stone to eke out an advantage, the authors give much more practical appraisals of openings, even if in most of these White can gain a theoretically guaranteed slight advantage with correct play. You’ll see White and Black wins in these games. Whenever possible, they try to give you the original debut of the opening, followed by at least one modern example of the opening.

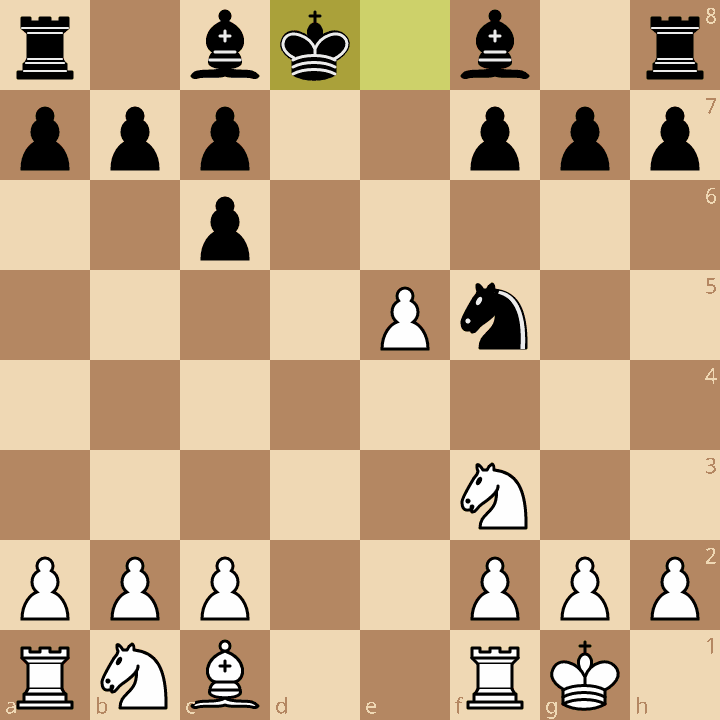

The meat of this book is in the Berlin Defense games (3…Nf6) where the “Closed variations” (e.g. 4.d3, or “Anti-Berlin”) get a nice exposé, and then the very theoretical Berlin Wall Ending (or “Berlin Endgame”), as well as attempts to avoid it. This was by far the most technical section of the book, but it also contained some of the best games. In fact, by and large, all Berlin selections were rather well-chosen. Some are as recent as the 2022 Candidates tournament. Lots of explanations of the 4.d3 Berlin here. As a player who employs that line personally, I liked the coverage they gave here, but other folks can enjoy the games even if that’s not their style, since the closed nature of the opening leads to many possibilities.

After the 4.d3 lines, we get the Berlin Wall segment which I found surprisingly enjoyable. People call this endgame “dry”, but I wonder if this is just the sort of thing that people say when they dislike queenless middlegames (which is what these are probably more technically described as). There’s even a bit of a miniature story told about the Kasparov-Kramnik rivalry in which Kramnik infamously held Kasparov to a draw with the black pieces in every game by digging up the Berlin from its early grave in the 2000 PCA World Championship. You’ll see Kramnik frustrate Kasparov multiple times, but then see Kasparov finally get his revenge. And there’s an amazing attacking game by none other than Ian Nepomniachtchi against Hikaru Nakamura which expresses Nepo’s typical brilliance, a true wonder to behold. We also get plenty of games from former World Champions Anand and Carlsen. We also get once very nice example of Stockfish vs Alphazero, which is surprisingly instructive, but also very entertaining. We also get one famous Paulsen - Morphy game in the Four Knights Spanish, which opening admittedly is oddly placed as the end chapter — a bit of a theoretical anticlimax. However, putting it in the context of the Berlin (where White can respond with 4.Nc3 and transpose) isn’t the worst way to fit it in.

The authors rarely ever get ahead of themselves, and it’s a nice treat to see Lakdawala show off some of his own games to give us more realistic examples of how the games can go as well. This is where Lakdawala’s self-deprecating humor hits more than misses.

Conclusion

One effect of going through a wide berth of opening theory is gaining an appreciation for ideas that you wouldn’t normally consider. If I have a fault as a player, it’s my tendency to be a straightforward player, to try to stick rigidly to a plan once I have found it. But to become truly great at this game, you need to be creative. And this book shows a lot of games in which players went off the beaten path on their way to rediscovering particular variations and learned to make something new. Playing through these games was the reward in itself, but I can see how many of the ideas, especially from the Berlin endgame section, can make their way into my games without me having to try really hard. Just seeing what’s possible can positively affect your game. My one real complaint is the jarring commentary when Cyrus tries to fit a joke in, but by the end of the book this habit appears to have been curbed a bit somehow. Like I said, your mileage may vary.

This book isn’t trying to be a repertoire — it’s a collection of 51 model games that I think any club player planning on building a Spanish repertoire (with either color) should consider getting and perusing, since you’ll have examples from the 1800s up to the 2020s. The truth is, I’m not entirely sure where this slots in as far as other opening books go, but I do know that model games and learning from master practice are classical tools for improving at chess and I can’t imagine my chess got worse through reading this book. As usual, I found some very inspiring moments among these games that put a smile on my face, and in the end that’s what chess should be about.